“I Have Been Accused of Being Conscientious About Trifles…”

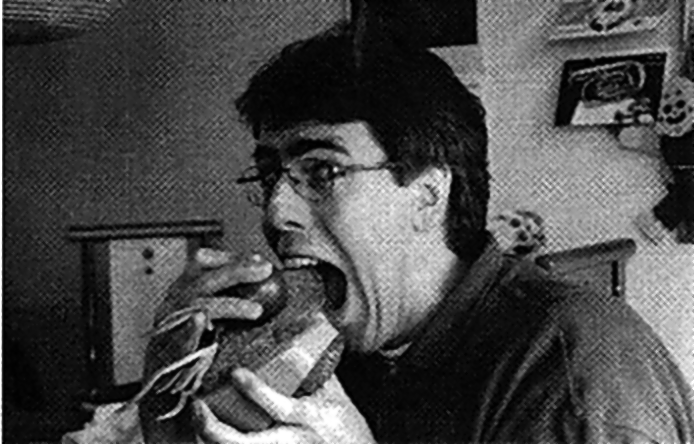

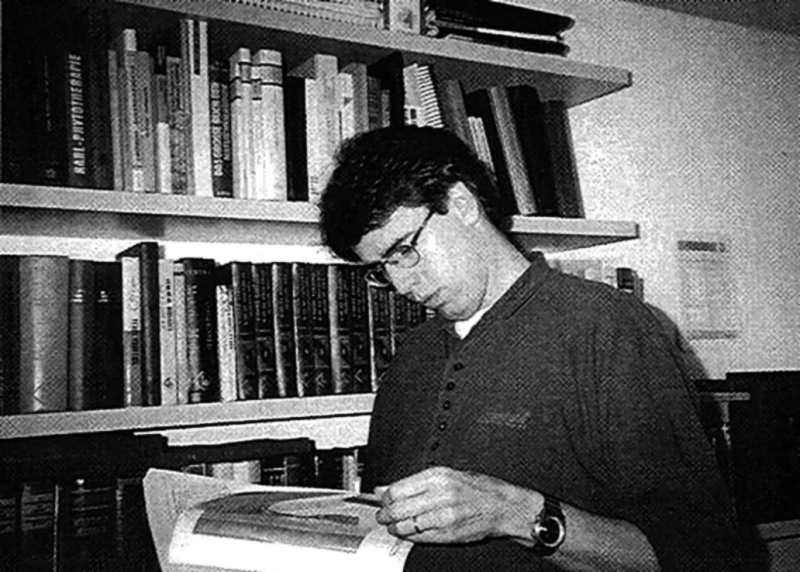

An interview with Roger van Zandvoort

The American Homeopath (Interviewer Greg Bedayn for AH), Spring 1994

For all homeopaths, choosing a repertory requires careful consideration; sometimes it takes years for a practitioner to find the repertory that works best for them.

The most essential requirement in choosing a repertory is the reliability of the information found within it. Many repertories have been published in the past 150 years, some more useful than others, and some more accurate than others.

Roger van Zandvoort, from the Netherlands, is widely recognized as a relentless researcher for his extensive work, The Complete Repertory. Roger has gone to great lengths to make his repertory as reliable and thorough as possible, with many thousands of additional and previously uncorrected rubrics and remedies. His methods and reputation for accurately assimilating homeopathic information are among the highest in the history of homeopathic repertory research.

—Greg Bedayn

AH: Tell me about yourself.

van Zandvoort: I am 35 years old, born on November 30, 1958, in Heerlen, the Netherlands. That’s in the south near Maastricht. I just graduated from high school; I started attending gymnasium for two years, and then I was kicked out. I graduated from high school at the age of 19.

Then they called me for the army, so I went. Initially, I wanted to study either medicine or biology. I was already accepted into biology at one of the universities, but after the army time, I thought, “I am not going to study; I would have to study for a long time.” That was not my idea of what I should be doing.

AH: How did you come to homeopathy?

van Zandvoort: Well, I was interested in herbal medicine, and I ended up going to a naturopathic college nearby in Hilversum.

I have always been a kind of collector; I like collecting things. I started collecting butterflies when I was really young. I still collect butterflies; now I catch them with my camera.

While busy with that, and as homeopathy was part of the study, I discovered that Boericke’s Materia Medica contained a wealth of information on herbal medicine. This gave food for thought: it meant that a significant portion of homeopathy's roots stem from herbal medicine. That was the start, and then I began refining my homeopathic study.

I met my wife, Anne-Marieke (Wiekie), there, in my second year. She was one class higher than I was at that time, and she had never seen me before because I was continuously printing study materials in the school's basement. They had a printing machine, an offset machine there.

AH: Printing for yourself?

van Zandvoort: No, for everyone. In those days, it was poorly organized. There was a lot of material lying around, but none of the teachers were doing anything with it. So I collected all the material and reorganized the whole thing, and started printing materials.

AH: That’s got a familiar ring to it. Is that when you started your compilation work?

van Zandvoort: I have always been a kind of collector; I like collecting things. I started collecting butterflies when I was really young, and later on I started collecting cacti and other plants. I still collect butterflies; now I catch them with my camera.

AH: Did you collect medicinal plants?

van Zandvoort: Oh, many, yes, which led me into teaching herbal medicine. I still have every piece of study material that we had in that school. I collected it. I had the most extensive collection of study material that even the teachers had seen. And later on, I made sure that the school had a copy of all of that.

But then it got mixed up again. I came back years later and went to look at it, just to have this feeling of whether or not I really did something, and it was scattered entirely again. So it wasn’t really worth it, but I still have all that material. Many people have copied it, so they must be happy with it. It was difficult to collect all that stuff.

AH: Some people seem to like copying the results of your hard work. Is this a recurring theme?

van Zandvoort: Yes, I will get to that. So, I finished school in ’83, but I was still connected to it. I was coordinating the weekend courses that we had, and then I started teaching herbal medicine. I translated some herbal medicine books from German. I created a compact Dutch version from German.

I had a lot of herbal medicine books by that time, and I wrote some study material for the school that they used while I was still a student there. They used it for several years after that. I had already completed three years of classical homeopathy by that point. So Wiekie and I started our own practice in 1985. Before that, we had only slight practice experience with more seasoned colleagues.

AH: So the two of you opened up a consulting practice together?

van Zandvoort: Yes. We moved to our current location and started our practice. It worked well, and we practiced for several years. I was still connected with the school, but it became less and less.

We spent most of our profits on following homeopathic classes all over the world. We went to Greece to Vithoulkas, then we saw him here in Holland. We went back to Greece three times to study with Vithoulkas, and once to England to the school where he was teaching.

In our practice, we first treated most people with herbal medicines. However, when we felt we had identified the correct homeopathic remedy, we would administer it—but only when it was clear to us.

AH: Otherwise, you wouldn’t give a remedy.

van Zandvoort: No, we felt that we should not give remedies that don’t have any effect, because then people don’t come back to you. So we were cautious with that, and we built up our practice in this way.

But after a while, it meant that nearly our entire practice was homeopathy. And for that reason, I bought a computer in 1987, and I purchased MacRepertory to help me in my practice. It was a Macintosh SE.

AH: Had you met David Warkentin yet?

van Zandvoort: No, not yet. I got MacRepertory, and I was comparing the information that Bill Gray had with the Vithoulkas additions to the Synthetic Repertory, and I saw that there were many differences. I liked the Synthetic Repertory, so I started collecting material to add to MacRepertory. I started building that up.

And I saw that the authors were not always the same, although they had the same additions. That’s how I became involved in finding out where these additions really came from. That’s what I am still trying to find out.

AH: Where does one look?

van Zandvoort: Well, you dive into the materia medica. You have to. Or you dive into the other repertories. That’s another possibility. It’s best to do both.

Because what you see, sometimes, in the repertory, is that there is a specific rubric that is not completely clear, but has particular remedies that you would like to add in, and you don’t know exactly where to place it in Kent’s Repertory. So you must look up these remedies in the materia medica and find out what the rubric really was, and then decide whether or not you’re going to add all that new information to Kent’s Repertory, and if so, where.

AH: So you had to rewrite parts of Kent’s Repertory in order to fit all the new information.

van Zandvoort: Yes, I started to put in lots of information. Initially, I was primarily focused on making it as big as possible. There is really quite a lot that anybody can add to Kent’s Repertory. Many people told me afterwards, when they had The Complete Repertory, that they felt naked using just Kent’s.

AH: How were you able to keep everything in order—all the repertories, materia medicas, journal articles, authors, and their sources?

van Zandvoort: I remember from earlier days when I was studying, that everything had to be there on my desk—all the materials to be sure that the study could be complete. Pencil, paper, everything neatly organized, the right books, so I had all the information that I needed on the subject that I was studying.

This didn’t begin for me with the study of homeopathy; it’s a general truth for me. With the herbal medicine, I saw that much of the information we had was disorganized, and so I started compiling my own database to make sure that everything was there, so I didn’t miss anything.

So that kind of thing continued with me. I didn’t want to miss anything. There’s an awful lot of information missing in Kent’s Repertory, and that’s one of the reasons that I began this work.

So that’s how it all started. One of the most useful tools has been MacRepertory for doing the repertory changes. That has really been a great help. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be very far along in this task. I made sure that each research group would use MacRepertory to make it easy for me to keep track of the various research I was directing. It was the perfect database.

AH: How many groups are doing research for you?

van Zandvoort: The most important three were the Boericke group, the Phatak group, and the Boger/Boenninghausen group. Most of the other research has been done by me.

I have all these shortcuts with macro-keys, etc. It’s like clockwork—very organized and precise. I know where to put everything so it stays organized. There’s not too much that I have to look up anymore. If there is doubt, I use ReferenceWorks to find where to place the information in the repertory. I use ReferenceWorks every day for that purpose.

So that’s how we started doing that. I was busy doing this compilation just for our own practice. Kent did the same—he did all his work for his own needs, in the beginning, to use in his practice and lecturing, etc. It was his students and his colleagues who pushed him to bring it out, to publish it.

At a certain moment, I became involved in selling MacRepertory in the Netherlands and Belgium, which I still do.

AH: When did you meet David [Warkentin]?

van Zandvoort: May 1, 1988. David came by, and we met when I became a dealer for MacRepertory. David said, “What you are doing here is great; you should sell it.”

There were some things in MacRepertory with the repertory changes that didn’t work. For that reason, I went to California to ensure that everything I had done by then could be incorporated into the already complex program that David had started. I had to ensure that everything worked well.

In the meantime, I’ve been working on the new version, the 3.0 Complete Repertory. I like it as it is now. It’s a very good repertory, much more accurate than the former one, and much bigger.

AH: How much bigger?

van Zandvoort: About 50 percent bigger—it has nearly twice as many rubrics as Kent’s original. And in terms of additions, it currently has nearly 350,000 additions, where the version you still use has something like 180,000. So that has nearly been doubled. And better additions—more correct, more accurate.

AH: So, you have confirmed all the additions from the materia medicas and original repertories, but what about the journals?

van Zandvoort: I have used the journals when I could lay my hands on them. That was a difficulty until I met you and Hans Jorg Hee, one of the conservators of the Pierre Schmidt library.

The old journals are very important, as we know from André Saine, because they contain a lot of excellent information that we don’t have anywhere else. I’ve already copied some articles from the Schmidt library where the whole article is just this small previously unknown repertory—a repertory on the prostate gland, another on the urinary tract, etc.

Many of these smaller journals have disappeared, and there are very few complete collections left. So now what I am doing is collecting all this repertory information, sorting it out, checking its reliability, and entering it into The Complete.

AH: Have you been to the University of California/San Francisco Medical School library? They have one of the largest collections of homeopathic literature.

van Zandvoort: David gave me a list of what they have. I also have an index of the books that are in Pierre Schmidt’s extensive library, and an index of Julian Winston’s books. Recently, Julian sent me Stapf’s additions.

Hahnemann’s Materia Medica Pura—Stapf had put together a collection of provings of different remedies and additional information about existing remedies that came from Hahnemann. And you can’t find that book anywhere. Pierre Schmidt didn’t have it, even in his library, but Julian had it!

What I mostly do is carefully read the preface and introductions of a new book, much more so now than before. They contain valuable information about what the book was based on, where it comes from, what the information has been taken from, etc. If it’s a repertory, it says it’s based on this or that materia medica, and with the later materia medicas it says sometimes where, for example, the original provings came from.

As an example, Clarke is what we call a secondary materia medica. His dictionary is based on the proving materia medica, the primary materia medica. However, because it’s secondary literature in homeopathy, the structure of the information on the remedy is much more organized than the structure in the originals, which simply list the provings. That’s why, for example, Clarke and Boericke’s materia medica are so useful, because they have a clear structure.

However, Clarke also offers proving information and new remedies that no other materia medica has. If you know this, then you can add in that information; you know where to find it.

AH: How many repertories have gone into The Complete?

van Zandvoort: Close to forty repertories and materia medicas, along with all these other articles. I used a lot of small, sometimes very small repertories because, based on the practitioners they came from, they could be considered reliable.

What I actually should have done earlier is to start with that material which was the oldest. Later on, I started to do everything in historical order, to ensure that all the additions we have really go back to the first person who ever mentioned them, for reasons of accuracy.

Some homeopaths then, and today, are revisionist in what should be purely transcription of previous findings. The information is sometimes inaccurate. This is why we list the sources of all remedies in The Complete. It makes the information more reliable if you believe the source is credible.

You will find in almost all repertories, even new ones, that certain remedies are, for whatever reason, put into the wrong rubric. And if you are going to use that information to prescribe for a patient, you would be missing the simillimum. People’s lives depend on the accuracy of our literature; this is why I have been so painstaking in researching, then listing the sources, or providing the symptoms in the provings. These remedies are absolutely known to have cured these symptoms. We searched through all the literature, wherever we could find collaboration, based on articles written by reliable practitioners.

AH: What are some of the classic drawbacks of repertories?

van Zandvoort: Well, a repertory is an index to the materia medica. It’s the back pages of the materia medica, so to say—a register.

To create a good register, the things you find in the materia medica, to be put into the index, have usually been cut up into smaller pieces. So what you usually don’t find, at least in Kent’s Repertory, is a complete symptom, including modalities, in one piece. It’s cut up in pieces.

It means that you can find all the information that is in the materia medica, but it’s in loose pieces and difficult to use. You should always go to the materia medica afterwards to confirm the remedy so all the pieces knit together and become a cohesive picture.

To give you an example, you could have a patient that has, let’s say, frontal headaches with stomach pains. You repertorize that and out come two remedies—let’s say Arsenicum and Nux vomica. Now you go to the materia medica and you see that Nux vomica has frontal headaches, but not in combination with stomach pains. However, it can cause stomach pains, but these are not related to the frontal headache.

However, you can see that Arsenicum has frontal headaches in combination with stomachaches. So that’s your remedy. But that’s something you only discover when you return to the materia medica.

There are many things like that which are not in Kent’s Repertory, so we have added a lot of information of that type. Boenninghausen has a lot of these concomitant symptoms—symptoms that happen at the same time in another part of the body and go together. So that’s very valuable information.

Since we have added Boger-Boenninghausen’s Repertory and Boger’s Synoptic Key, you will find more secure information inside The Complete Repertory. In the Mind section, for instance, we used Knerr’s Repertory, which is well known for its exact quotations from Hering’s Guiding Symptoms materia medica.

Right now The Complete has close to 350,000 additions.

AH: What actual changes in structure have you made to Kent’s Repertory?

van Zandvoort: Some of the changes in structure were actually Kent’s work, but they were never published. It is found back in the final General Repertory, the one that Pierre Schmidt and Hari Chand made.

There are some more changes that we did that were not in Kent’s Repertory. We moved the dreams from the Sleep section into the Mind section because many of us felt it’s all mind stuff; it’s just happening while you sleep. Dreams are all about digesting impressions of the day, and old griefs, and everything that has to do with emotional things and the subconscious. So that’s all in the Mind section now.

We talked to a lot of people about this, including psychiatrists who are also familiar with homeopathy. And most of them agreed.

We also combined some main rubrics in the Mind section. For example, you had the rubric “Talk,” the rubric “Talking,” and the rubric “Talks.” And if you see the subrubrics, you can’t be sure whether or not they really belong to what they are under. Are they under “Talk,” do they have to be under “Talks,” do they have to be under “Talking”?

So we combined them. Now it’s just Talk / Talking / Talks as one main rubric, and every subrubric that originally was divided in these three is just now in alphabetical order in one main rubric. It makes more sense. If someone really finds out which one should go under which, I would like to change it—but there should be a definition of the exact meaning of all of those.

Kent probably split it up for a good reason, but you can’t always find the reason, whatever it was. Kent used other rubrics that have the same meaning. You can see why he did it, because some repertories mention that specific name, and he just took that over. He used other repertories, and he didn’t always look back to see that he already had that information under another term in his repertory.

AH: The amount of work we can do in an hour on a computer with ReferenceWorks, compared to a person with a stack of books with pen and paper, is staggering. And imagining Allen and Hughes working together on Allen’s 14-volume encyclopedia through correspondence overseas, it seems unbelievable.

van Zandvoort: Yes, I know exactly. For Allen and also for Hughes, they collected material from others. It’s not only their work; it’s a collection, like Kent’s. They used each other’s discoveries.

It is hard to imagine that their accomplishments were possible, yet we know it happened. It would be nice to go back 120 years to see how it all worked. The other way around would be nice, too—to have Kent sitting here looking at the monitor, seeing what has become of his work.

AH: How many sources of information did Kent list?

van Zandvoort: That’s one of the things I didn’t like so much about Kent’s Repertory; he doesn’t list any sources. He says in some of his writings that he used Allen, he used this and that—he says it’s a compilation of sources that he used—but he’s not very specific.

AH: How about Künzli?

van Zandvoort: Künzli is specific on what he added to Kent’s Repertory, though not so much for the original Kent material itself. By being busy with The Complete Repertory, we’ve found out a lot of sources that have been used by Kent. He must have had a tremendous amount of information available to be compiled. So he and his students must have done a lot of preparing in order to make sure that he had all that information available.

He was a great compiler. And he had great insight into how the structure for the repertory should be, although he also had examples from the past for that.

AH: What do you think of ReferenceWorks in terms of replacing repertorization?

van Zandvoort: Most people that I’ve sold it to think that it’s a very nice tool for looking up information, but they don’t know how to use it as a case-saving program yet, like you can use MacRepertory as a case-saving program.

You can definitely find information in ReferenceWorks that is nowhere in the repertory. We had a case in Maui—Nancy Herrick did a case where Curare came out; I don’t think that remedy could be found listed in the repertories at the time. That remedy cleared the case. Of course, later on we can put in all that Curare information, and then it will be better—but it’s not there yet.

So, within who knows how long, we will have a lot of that type of information logged in.

AH: Which smaller repertories have you used in your compilation, and how do you choose one over another?

van Zandvoort: I used Jahr, Repertory of the Heart by Snader, Facial Neuralgias by Lutze, all very good repertories. André Saine gave me a whole list of repertories years ago that had, according to him, reliable information. I’m busy collecting all that information.

André has the book reviews from all the old journals in his collection. From these book reviews we can get otherwise obscure information about books, authors, and in-house politics. They, too, had rubbish-books a hundred years ago, of course—and also excellent books. The early reviews have been a big help to all historians of homeopathy.

Ten years ago I didn’t care about what was written in the introductions to The Synthetic Repertory or Vithoulkas’ Essencesor whatever. I just went for the book, and that’s it. Now, that part of the book, before the actual book begins, is very important. Because there you find the clues that you need to decide whether or not, or how, you are going to use it.

So what we would like to do is complete all the chapters of the repertory with all the reliable information we can find, especially from the repertories, for one main reason: since it’s already a repertory, it’s easier to add into The Complete. If it’s a materia medica, there’s much more work to do. Those people already did part of the work for us; they cut it into pieces already, so it’s easier to chew.

That’s the main reason that we use repertories a lot more than materia medicas. But for verification you have to go to the materia medica.

So what we need to do later on, for example, is have one complete repertory on, let’s say, throat–nose–ears, and a complete repertory on the digestive tract—stomach, abdomen, rectum, stool. Logical combinations of chapters, to bring them out as separate books.

In The Complete, there’s actually one section that many people don’t know about. It is the Relationships of Remediessection, and it’s greatly expanded in the new version of The Complete. All abbreviations that we have would be there, if possible, with the family name, or the English and Latin names, and what the tinctures are made from.

We put in relationships of remedies as found in Knerr’s Repertory. Knerr gives much more than R. Gibson Miller, who didn’t use degrees of remedies.

You can have a look in Boger-Boenninghausen’s Repertory, the last part that has the concordances, which are remedies that follow well, divided in groups. He gives, as an example: suppose you have given Aconite to someone; it worked well, and he’s left with some symptoms that you have to translate to rubrics to find the follow-up remedy.

What Boenninghausen has done is divide these symptoms in groups, so if the main symptoms left over after Aconite worked well are mind symptoms, he found out which specific follow-up remedies come forward more for mind symptoms after Aconite. And he has found out which remedies come out more when they have extremity symptoms, digestive tract symptoms, circulation symptoms, or sleep symptoms.

That’s all in The Complete. I have to write something about it, because most people won’t know how to use it. It can be very useful. Suppose you have just done a normal repertorization with the follow-up symptoms, and you are completely in doubt about, let’s say, three polychrests that you have to choose from. Of course, it’s always good to study the materia medica, but you can, in this case, also go to the Relationships of Remedies section and find out which of these three polychrests is the most logical if it’s about mind symptoms after Aconite—and which one is about extremity symptoms after Aconite. It will be there.

What I would like to do is make that a separate book, too: The Complete Relationships of Remedies. There are many authors who write about that. Lippe has a lot of information about it, Jahr has a lot of information, of course Knerr, Hering, Clarke—everyone tells you something about it. And it’s important. We know some of it, but there is more.

AH: How many hours did you put in, working on The Complete?

van Zandvoort: Seven years in combination with practice, but I was working until eleven o’clock most nights. I don’t do that anymore. Now it’s only about sixty hours a week.

AH: Over 12,000 hours!

van Zandvoort: I told David; he didn’t believe me at first.

AH: So how did things develop with David?

van Zandvoort: We became very good friends.

AH: And you collaborate?

van Zandvoort: We have this ongoing adolescent to take care of—MacRepertory. It has one father and, let’s say, a brother who helps. That’s how I see it. David and I have the same kinds of interests. He loves nature and I love nature, too. So we have the same kind of thoughts about that. We became friends quite easily.

He came to Holland to see his MacRepertory representative for Holland and Belgium. We met and it clicked. He stayed in our house and didn’t go out because it was raining all the time! It rained for days, so we had a lot of time to talk and drink a lot of Belgian beer. And it was fun; David wasn’t used to this. Our wives became like sisters, very good friends with each other.

I have ongoing contact with David, and there are a lot of things that I’m giving my opinion on. I was the European coordinator for Kent Associates; I had to stop that because it was too much work. I love to do all that work, but it became too much. So I stick to something that I love, and I also make sure I can make some money with it. It’s important to make a living out of it.

AH: So, what’s next for your family?

van Zandvoort: We have to move. That’s very important. Our house is just too small.

AH: Where would you move to?

van Zandvoort: Hilversum is small, quiet, there’s more nature, it’s not so crowded with people. It’s a nicer area to live. Where we live now is a very crowded area. Holland is such a small country, and it has fifteen million people.

I mean, Paris, which is a big town, is as big as one of our provinces. So take Paris and multiply it by fifteen, and you have Holland. With my love for nature, in general, it’s the wrong place to live. There is no nature—only parks and cultivated stuff.

Since I am my own boss, I have to put in a little discipline to be sure that everything works well. No one is going to criticize me if I do anything else—except Wiekie, but she doesn’t do that too easily. Mostly I make sure that I am in my office, which is just downstairs, at about 9 a.m.—could be a little earlier, could be a little later.

I start browsing through Homeonet and whatever we have, and see whether or not anything new is there, whether or not I had any messages, any letters, whatever—or look at my incoming faxes, etc. And I have this pile of papers, and I just start working on The Complete with whatever is left from the evening before, which is mostly the Swiss corrections right now, on the Mind section, because that has to go out as soon as possible. And underneath there is a lot of information that comes from Pierre Schmidt’s journal collection, that I still have to work on.

There are lots of phone calls every day from all over the world, mostly colleagues about The Complete, and also MacRepertory.

In the morning I just eat some muesli and drink some tea and I go to work. At around 11, I stop and have a cup of coffee with Wiekie and I go on till about 1, have a break, eat something, and go on again until about 5 or 6. I prepare the table for dinner, while Wiekie is cooking. Later on we eat, I do the dishes, sometimes some television with Shivane. She comes downstairs sometimes to look at the computer and see whether or not everything is fine—she really does that! Then she goes up again.

Sometimes I work until, not later than, let’s say 9 o’clock. That’s it—a quiet life. I watch television, read some. There are always seminars in between. Holland is having a lot of seminars, and Germany too—it’s becoming less now, though.

AH: Do you see Geukens?

van Zandvoort: I see him a lot; when he has seminars I will be there a couple of days. I don’t go to all these seminars constantly anymore. We have two other people helping me demonstrate MacRepertory, so I don’t have to go to all the seminars. It would be too much, because there are so many.

And then I have to make sure, these days, that I stay in touch with the homeopathic teachers we have, because they are also good indicators about what people want; they have good ideas about what a repertory should be like, etc. It was great to meet many of these people once more in Maui, and ask them their opinion, have some quotes that we can use for MacRepertory and for The Complete. That’s how it works.

Then every once in a while, let’s say three to four times a year, I fly to Switzerland and connect with the Swiss group for a couple of days. The Swiss group is mostly people that all have MacRepertory and who offered to help me, years ago, in correcting the Mind section. They wanted a good repertory to work with.

It was actually based on Künzli’s idea of making a more complete repertory. This group tried to convince Künzli to make use of The Complete Repertory. And actually they began working on that, and then Künzli died. So he never had the opportunity to see his idea come to light.

When Künzli died three years ago, I had met with him twice, and talked with him—not enough; I would have liked to have talked more, but I lived in Holland and he in Switzerland. But this study group that he had, with all these people, they had a very good connection with him.

The two people that had the best connection with him, Dario Spinedi and Hans Jörg Hee, are now collaborating with me. We had a pretty good idea about what he wanted. All that Boger-Boenninghausen stuff he registered. Künzli created the organization for incorporating Boger-Boenninghausen into The Complete, although he’s gone. All the work was already done on paper, but not yet programmed into a computer.

It’s mainly six people that help me, and I’m busy setting up a collaboration with more people; the total number of people helping me in Switzerland, Germany, and Austria will come to about forty-two. I am still looking for people to do more work. And that’s not too easy. There are not too many people that have the skills to do this kind of work and who have the time.

The people that I would like to do the work are usually the busiest homeopaths, and it’s difficult to ask students to do these things. I was still a student when I started to do this, so it is possible. You have to look for people that know their stuff and know how to find information in Kent’s Repertory, and now also how to find information in the computer repertory.

So it’s mostly people that already have MacRepertory and have experience with the computer and know how to work with it. I am interested in hearing from people who would like to collaborate with me on this project. They should be people with experience; they should be interested in historical structures and those kinds of things—not because they’re apt to do something with it, but because of the motivation. That’s important.

Preferably they should have MacRepertory, because then we would be speaking the same language.

AH: What do you do for fun?

van Zandvoort: I love to go to movies, also at night. I’ve seen so many of them. You can put me in the middle of a movie that I didn’t see before and I’ll tell you the story in ten minutes—at least what has happened before. Not always the end, but I’m a good guesser about its ending also.

I like nature documentaries a lot. I don’t like the old movies too much. A good thriller is always nice—Dracula, the new version, was very exciting.

We go hiking and we have these beautiful islands in the north of Holland. To go there is a real treat. It’s beautiful. It is all natural, and it has a tremendous amount of birds. It is one of the places in the world to look at birds, especially during the annual migrations.

AH: What else do you have in your life? Do you race motorcycles or horses—anything like that?

van Zandvoort: No, no. Food—let’s get onto food! I like all food in general. Wherever I am, if I see something I don’t know in a restaurant, that’s probably the thing I’m going to order.

Exotic fruits, tripe, those kinds of things—different. What did we have in Greece, on George’s island, on Alonissos? Oh, lamb’s brains, slightly grilled. Good stuff! The only thing I don’t like is cucumbers; they’re too watery. If they’re really fresh, so they’re still crispy, that’s okay—but within five minutes, they’re not that crispy any more.

Wiekie is a good cook, and I like to cook, but there’s not much time to do it. I’ve done it more in the past than I do now. But I like to, especially if we have some friends coming over. That’s one of our main hobbies too—visiting friends, friends coming by. On these occasions, I love some good wine and, after dinner, a good cigar and philosophizing about life. I like that!

I collect butterflies by photography. Vanessa cardui—cardui stands for Carduus, like in Carduus marianus—a butterfly of the Nymphalidae family that has caterpillars that feed on Carduus. The ones that I like especially are the butterflies in the Papilionidae family, the Swallowtails; the Saturniidae family (like the Emperor moth); and the Sphingidae family (like the death’s-head hawkmoth and the hawkmoth).

AH: What is your home like?

van Zandvoort: Our house has a nice view on one side of a canal. The canal was built by the Romans; it’s quite old. It goes from Delft, an old university town, to Leiden, another old university town.

We see boats going by, so every once in a while you see these huge ships that just can barely fit, and the bridge where the people stand with the steering wheel is just at the level of the first floor of our house. We have enough of a yard that Shivane can go outside and play.

The house has two practice rooms, a waiting room, restroom, lockers with all kinds of stuff, and the first floor is the living room; the second floor is sleeping area. So it’s a nice house, but it’s quite small. We would like to have a room for guests and more space for ourselves. My room is popping out with books and stuff: computers, books, files, boxes, pages of God knows what…

AH: What is homeopathy like in Holland?

van Zandvoort: Homeopathy in Holland is quite well established. There is still no official recognition, but there are many doctors and non-doctors practicing. Classical homeopathy is well represented amongst the 2,000 or so homeopaths, and the level of those that practice classical homeopathy is quite high.

Holland, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland are the best-developed countries for classical homeopathy in Europe at this time. The doctors are the best organized, and the non-doctors have several organizations that will be united into one in the next year. There is a lot to do about homeopathy in the European Community, and many groups try to establish European rules their way. Lots of politics are involved.

AH: What are your plans for the future?

van Zandvoort: My personal plan is to further refine The Complete Repertory, which will take me many years more, and I would like to set up a kind of service where colleagues can ask about specific information they need for their practice.

My vision for homeopathy is that it has a great future, but it is hindered in its development when governments do not want to see that homeopathy can help them overcome the problems they have in financing health care in general. It will need a lot of lobbying and “scientific proof” before it will emerge as the main sort of health care for the future.

Already, you could say that by using compiled repertories and programs like ReferenceWorks, we are well on our way to being better organized, in terms of consistent information, than regular medicine. Now we must ensure that we can utilize this fact to promote homeopathy to the skeptics.

Add comment

Comments